I kept looking and I have found some impressive works in Staphylinidae, Scarabaeinae and Leiodidae, all of them groups fairly close to the Hydrophilidae, that have illuminated the path for me to understand what I'm seeing.

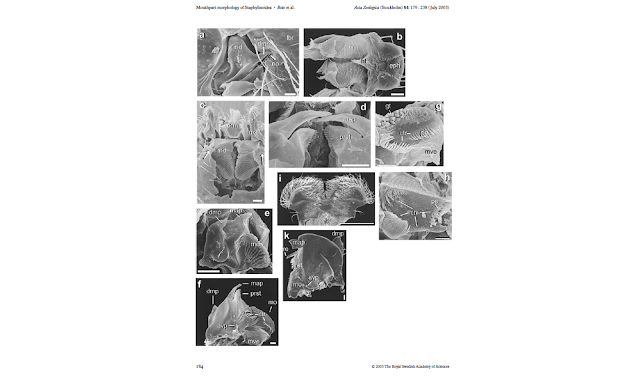

Betz, Thayer & Newton in 2003 published a very thorough survey of the mouthparts of sporophagous staphylinids. For the most part, they used Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) in order to illustrate the different kinds of variations in the components of the mouthparts, and included descriptions of their main functional elements, as well as a discussion on the structural and functional requirements for different feeding habits.

| |

|

|

| Weide et al 2014, part of figure 3 |

|

| Tarasov & Génier 2016, fig 42. |

|

| Antunes-Carvalho et al 2016, figures 3, 5 and 1 respectively. |

- Regular photographs through a microscope work very well, but are problematic when the structures have certain volume and/or overlapping parts and/or lots of setae, because when you stack a series of photos, the resulting image loses resolution in terms of the structures that you can see. The advantage is that as your structures are likely floating in glycerin, you can easily look at them in the scope and move them around as you please, and the issue of them sailing away when you are trying to photograph them, is easily solved using denser solutions as hand sanitizer or KY gel.

- SEM images are amazing for recognizing areas with different surfaces, different kinds of setae, distinguish arrangements of those structures, but sometimes you cannot tell apart sclerotized areas from membranes, let alone the concealing of internal structures. Other drawbacks include that the required drying process can distort the samples, and then mounting tiny pieces in SEM stubs is probably tricky and once the sample touches the sticky surface, there is no way to re-accommodate without ripping off things. So basically you should think carefully what view is the most informative, which is a straightforward decision with fairly flat structures, getting complicated with bulkiness. Another issue has to do with the cleanliness of the sample; sometimes structures get obscured by a layer of whatever the specimen was eating when it was collected. This issue can be easily solved with large specimens/structures, but is almost impossible with too tiny samples.

- Using micro-CT scan would be great! I mean, that's the dream! but the availability of the equipment for that is still very limited (and probably expensive); also, it seems to me that assembling and interpreting the resulting reconstructions takes time (I guess until you get used to do it). Advantages of this method have to do with the fact that is a non-destructive method that only requires specimens to be dry to the critical point; so you can even study old holotypes without even touch them, which is pretty convenient.

The fact that different works have employed different imaging techniques is helpful, but somehow it adds another level of complexity, given that making comparisons gets tricky, not only because you are comparing the same structure portrayed using different methods, but also because you are comparing taxa that even being fairly close, exhibit striking differences.

Even with the accuracy of the imaging techniques used across works, it is definitely so much better to look at the structures directly!! Don't get me wrong, authors really make an effort to show precisely what they see, but is not the same to look at a nice picture, than to be able to see the structures in the actual specimens and say "aha! it is exactly like in the picture!" It happened to me with the labrum of the Scarabaeinae as illustrated by López-Guerrero & Zunino (2007): only when I saw it in the specimen I realized how sort of reduced and highly specialized the structure is!

Here is an example of the mentum and all its wonders, indicating one of its associated sclerites, as viewed in an staphilinid, a dung beetle and Globulosis... all strikingly different from each other!!!

At this time I think the best approach would be to name and describe everything I see, noting how they compare to works in other groups, so if anyone gets to check on those structures in the future, she will know where to look. I guess trying to establish homologies at this point, without a developmental basis, could be misleading (even if "only" implied by the use of names in common).

On a last note, I really wish I had a colleague to discuss this things with...

References

- Antunes-Carvalho, C., Yavorskaya, M., Gnaspini, P., Ribera, I., Hammel, J. U., Beutel, R. G. (2017). Cephalic anatomy and three-dimensional reconstruction of the head of Catops ventricosus (Weise, 1877) (Coleoptera: Leiodidae: Cholevinae). Organisms Diversity & Evolution, 17: 199.

- Betz, O., Thayer, M. K., & Newton, A. F. (2003). Comparative morphology and evolutionary pathways of the mouthparts in spore‐feeding Staphylinoidea (Coleoptera). Acta Zoologica, 84(3), 179-238.

- López-Guerrero, I. & Zunino, M. (2007). Consideraciones acerca de la evolución de las piezas bucales en los Onthophagini (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) en relación con diferentes regímenes alimenticios. Interciencia, 32(7), 482-489.

- Tarasov, S. & Génier, F. (2015) Innovative bayesian and parsimony phylogeny of dung beetles (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae, Scarabaeinae) enhanced by ontology-based partitioning of morphological characters. PLoS ONE 10(3): e0116671.

- Weide, D., Thayer, M. K., & Betz, O. (2014). Comparative morphology of the tentorium and hypopharyngeal–premental sclerites in sporophagous and non‐sporophagous adult Aleocharinae (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae). Acta Zoologica, 95(1), 84-110.